Before we go any further into this blog entry, let me offer my apologies for the lack of activity here recently. Flu – the real, unpleasant, knocking at death’s door and asking for a priest to administer extreme unction type of flu – followed by the unwelcome intrusion of ‘real life‘ had curtailed my archaeological and historical musings of late. I have done a bit of research, identified a whole pile of fun things to blog about, done some poking about for more interesting sherds… but none of it is quite ready yet.

And so, I present to you, a bit of a cop out! A very short, and quite interesting cop out, but a cop out nonetheless.

As I may have mentioned before, I am obsessed with boundaries.

I love the idea of a start and an end to a physical place or space, and in particular I am fascinated by the ‘liminal‘ areas that make up the join between the two sides of any boundary. These are the ‘dangerous’ places, which are neither one thing nor the other, but somewhere in between, and it this space that has such significance in archaeology. This is where outcasts – the witch, the murderer, the suicide, the excommunicated – are buried, where dangerous activities take place, where the veil separating this world and the other is perceived to be the thinnest, and communication with the ‘beyond’ can be achieved.

One such liminal place is the junction of two rivers or streams, long held to be magical, and in some cultures believed to be a very powerful space.

Waterways themselves make great boundaries – they are by and large immobile, and they are very clear in their separation of the land (one does not overlook a stream, or one ends up with wet feet) – which is why, traditionally, they were used to define parishes and such. Indeed, it has been said that my own parish, Whitfield, is actually an island: it is completely surrounded – and thus defined – by streams.

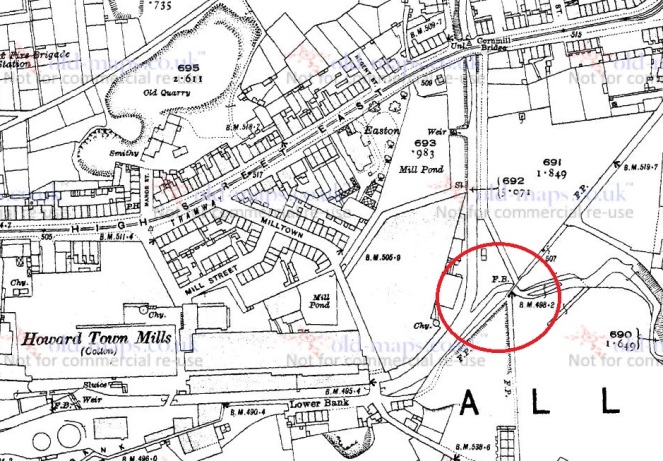

Glossop Brook is the boundary between Whitfield and Glossop, and it is formed by the confluence of two brooks – Shelf Brook, which flows through Manor Park from Mossy Lea and beyond, and Hurst Brook which comes through the Shirebrook Estate from the Snake Pass and beyond. They join here, at the bottom of Bank Street just before the footbridge that takes you to Manor Park

So, a liminal boundary that is formed by the joining of two brooks. Anthropologically, this is a powerful place, and one wonders what, in the deep and distant past, occurred here, or at least what marked this place.

This is the first in a series of posts that I’d like to do about Glossop’s waterways. Through their use as power for mills, they are quite literally the foundation upon which the modern town was built, and yet they are sadly often overlooked.

I shall be more attentive to the blog in future, and keep up the posting. Thanks for reading, and if there is anything you’d like to share, any comments or corrections, please drop me a line.

Whatever may have occurred in the deep and distant past, it didn’t occur here, but 80 metres lower downstream. On the 1857 Poor Law Map, the confluence of the two streams is just east of the bridge at Lower Bank. The Shelf Brook between Cornmill and Lower Bank was later straightened and shifted east to make room for the last phase of expansion of the Wood empire, the Great Eastern Shed.

This highlights the fact that virtually every watercourse in the area is largely artificial, having been straightened, widened, diverted and deepened to increase flow, reduce flooding, and create space for mills. The 200 metres of the Shelf Brook between the weirs in Manor Park is virtually the only remaining bit of more-or-less natural stream channel below the high moors. We know when some of this was done, and by whom, but not all of it, and in particular we don’t know how much was done by individual millowners like the Woods and how much by the Howard estate; some of the water supply arrangements are so complex and interdependent, with water flowing from one mill to the next, that it’s difficult to imagine that they were devised and constructed without, at the very least, strong oversight from the estate to prevent water wars between rival millowners. And did the estate do some of it as a speculative venture to attract investment in new mills? We know they did that in Hadfield and Padfield, where they built the Torside Goit to turn Padfield Brook from a trickle into a torrent, but did they do it also in Old Glossop and Howardtown ?

LikeLike